Summary

Overall Score 12 - Downgraded from 15

Political Risk: Downgraded 4/10

Economic Risk: Downgraded 4/10

Commercial Risk: Downgraded 4/10

The risk assessment of a country is made up of 3 components, being Political, Economic and Commercial. Each component is scored out of 10 with 1 being the lowest risk and 10 the highest.

Political Risk - Downgraded from 5 to 4

The military’s grip on the country appears under serious threat for the first time since it took control of the country in 1962. A rebel insurgency and campaign of civil disobedience has been gaining strength since the 1 February 2021 military coup that ousted Aung San Suu Kyi’s elected government.

The Financial Times reported in June 2022 that the military is now facing a “serious struggle to survive” as the insurgency against the army gathers momentum. The newspaper quoted representatives of the “People’s Defence Forces”, anti-regime fighting units that have sprung up since the putsch. But it also reported that foreign conflict analysts — including some who predicted the military would wipe out the PDFs quickly after the coup — have said the guerrillas were gaining recruits and weaponry.

Thousands of students, activists and workers have flocked to join ethnic groups, such as the Kachin Independence Organisation, that have been fighting the government for decades. The military regime has responded by attacking opposition strongholds with helicopter gunships, fighter jets, and troops that burn villages they accuse of supporting anti-junta militias.

Meanwhile, an expanded civil disobedience movement has paralysed the banking system and much economic activity. In February 2022 widespread strikes took place across the country with civilians joining monks to protests against military rule. In April, the population boycotted the normally boisterous New Year water festival.

In August, the military extended its emergency rule until 2023, a tacit admission that it is not in control of the country. The junta first declared a state of emergency after seizing power from the elected government of Aung in February 2021. The military has pledged to hold new elections in August 2023, but few believe they will be free and fair.

Opposition to military rule has also disrupted the government´s campaign to control the pandemic. Large numbers of medical staff have joined the civil disobedience movement and have been refusing to work for the military regime since last year’s coup. By August 2022, the government claimed to have fully vaccinated around 60% of the population. However, there are doubts about the real progress of the vaccine programme. Myanmar is also reliant on Chinese vaccines that have been demonstrated to be less effective against COVID-19 than their Western counterparts.

Economic Risk – Downgraded from 5 to 4

Myanmar is experiencing a severe recession as a result of the military takeover in February 2021 and the ensuing political unrest and violence that has disrupted banking and commerce. The country was already in recession prior to the coup: the pandemic took hold in 2020 and paralysed the lucrative tourism sector.

The failure to contain the spread of the virus has only exacerbated the slump. In January 2022, the World Bank reported that the economy was 30% smaller than it would have been but for the coup and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Independent forecasters believe the economy will experience anaemic growth or another contraction in 2022 – see the economic risk update for further details.

The coup has disrupted foreign investment significantly. Since 2011, approximately 90% of FDI in Myanmar has emanated from Asian countries, which have been steadily improving economic ties. However, in response to the coup and under pressure from activist groups and western nations, firms are restricting activity.

Japan, for example, has cut its aid since the coup and many Japanese companies have frozen their operations in Myanmar due to difficulties in operating business activities. Violence in and around workplaces, internet shutdowns and a scarcity of employees have led office spaces to shut down.

Many infrastructure projects have been suspended, causing a “very large contraction” in the country’s construction market, with the prospect of growth pushed back to the second half of the decade, according to a Fitch report in November 2021. Fitch cites Hong Kong’s VPower Group pulling out of two operational LNG power plants and Adani Ports withdrawing from its investment in the Ahlone International Port Terminal project.

China, however, is stepping up its activities in the country. It continues to push ahead with its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), even though resentment concerning China’s increasing grip on the economy and its support for the junta appears to be increasing across Myanmar. In February 2022, the UN human rights expert on Myanmar said Russia and China were providing the junta with fighter jets being used against civilians.

Commercial Risk – Downgraded from 5 to 4

Myanmar rates as one of the most difficult countries in the Asia–Pacific region in which to do business even prior to the military coup. It ranked 165 among 190, according to the 2021 World Bank Ease of Doing Business guide. This ranking has almost certainly fallen sharply since that report.

Since the coup, the banking system has been disrupted significantly. Sending money out of Myanmar is extremely difficult, with much stricter oversight by the central bank, harming international trade and commerce. Access to and use of the internet is more difficult, with internet shutdowns common, and the disruptive effect on business activity has been magnified by the coronavirus and the associated need for remote working. Privacy and data-security concerns have also increased. Entering, leaving and moving around the country are difficult, with safety concerns about staff a major issue given the deteriorating security situation in many areas of the country.

Meanwhile, government decision-making and the administrative process are much slower and less predictable, affecting even routine matters such as tax administration and visa processing. Senior government personnel in many positions have changed, while new policies have been adopted, and the civil disobedience campaign has severely disrupted administrative processes.

The rule of law has suffered further setbacks. Even prior to the pandemic, businesses reported very low trust in the independence of the judiciary, with bribes and irregular payments in exchange for favourable judicial decisions very common.

Corruption – already a significant challenge – has worsened as living standards have plummeted. Myanmar ranks joint 137th out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s 2021 Corruption Perceptions Index. The Myanmar Corruption Report by GAN says that corruption is endemic in Myanmar, presenting companies with high risks. The weak rule of law and complex and opaque licensing systems are serious barriers to investment and trade in Myanmar.

A lack of adequate infrastructure also provides significant challenges to operating in Myanmar. Sanctions levied since the 1960s have caused Myanmar’s infrastructure to become outdated. Much of the country’s electrical grid relies on hydropower, and factory operation, for example, becomes unreliable during dry seasons. While there has been significant growth in the country’s paved road network, the vast majority of the network – around 60% – remains unpaved. Meanwhile, port capacity is limited and the railway service depends on ageing and unreliable equipment.

September Bulletin

Political Risk – Downgraded from 5 to 4

Myanmar is now more polarised politically than it has been at any point over the past 20 years. As attitudes harden on both the military and pro-democracy sides, the prospect of a dialogue that could bring the two together recedes.

The military is shunning attempts by ASEAN and others to pressure it into engaging with the opposition. The junta’s execution of four pro-democracy activists in late July suggests the military is not ready to compromise. But the executions also highlight the brutality of the regime and will encourage the view among the opposition that armed struggle is the only way of removing the military from power.

The attitude of China is key. Beijing is the junta’s closest foreign ally. There are signs that China is playing a complex game in Myanmar, reaching out to the rebels in case they gain the upper hand. So, as well as sending vaccines to the government to distribute, Beijing has “also quietly shipped thousands of vaccines, medical workers, and construction materials for quarantine centres for multiple rebel groups”, according to the French news agency AFP.

Meanwhile, the increasingly intense guerrilla war in parts of the country may cause some in the military to question whether they can continue on the current path and risk losing all the economic and social gains of the past 10 years.

There are numerous reports that the army is suffering from low morale, with many soldiers, including officers, defecting to the rebels. It is also having trouble attracting new recruits. Moreover, a shortage of aging Polish-built Mi-2 and more modern Russian Mi-17 transport helicopters, vital in any guerilla war, is adversely affecting the army’s combat ability.

Once an army’s morale collapses and the opposition gains momentum, the end can come very quickly as we saw in Cambodia and Vietnam in the 1970s. On the other hand, if the rebels remain divided and continue to lack vital weapons, the war could drag on indefinitely.

The deteriorating economy could also have significant repercussions. People in Myanmar have historically taken to the streets in mass numbers when an economic shock makes their livelihoods untenable, and we may well be approaching that point. Around 40% of the population now live in poverty, having seen a decade of reform and progress reverse over the last two years. By August 2022, the price of rice, the staple diet, has increased by 45%, while the price of palm oil has nearly tripled since last year. At the same time, prices for basic foods such as onions and potatoes has more than doubled.

Another outcome is a diplomatic solution engineered perhaps by China. If that happens the best hope is that the military’s involvement in any new government proves very limited given their appalling record in running the country over the past sixty years or so. The emergence of a government - packed with technocrats that implements the economic policies that have enabled the economic miracle seen in the rest of Southeast Asia could yet occur.

Economic Risk – Downgraded from 5 to 4

Following an 18% contraction of the economy in the year ended September 2021, the World Bank’s Myanmar Economic Monitor, released in July 2022, projects growth of just 3% in the in the current fiscal year to September 2022. The World Bank, however, said some sectors had stabilized or recovered over the previous twelve months, driving the modest growth expected for this year.

However, Fitch Solutions, in analysis published in July 2022, forecast the economy would contract again this year, shrinking by 5.5% in the current fiscal year. The projection, according to Fitch reflected the impact of the ongoing post-coup conflict, compounded by the impact of “high global commodity prices and domestic inflation.”

Fitch added that real GDP growth would return to positive growth of 2.5% in FY2023, as global commodity prices and inflation begin to ease, “reducing some of the pressure on real household disposable income.” But given the low statistical base, it described this projected recovery as “meager.” Fitch also said it did not expect the economy to recover to a pre-pandemic level for at least another six years.

The World Bank reported that some firms had reported operating at a higher proportion of their capacity in 2022 than was the case in 2021, particularly in the manufacturing sector, and manufactured exports are recovering. Construction activity has also picked up as work on several projects has resumed after a long pause last year, and the pipeline of issued permits has grown. A rise in mobility at workplaces, retail outlets, and transport hubs has supported overall activity, although indicators of consumer spending are weak.

The World Bank says that the spike in inflation has disrupted the operations of all businesses. Increases in global oil prices have driven pronounced increases in domestic fuel prices and transport costs, as well as in the cost of running diesel generators to compensate for recurring electricity outages. Kyat depreciation, supply chain disruptions and the spillover effects of higher transport prices have resulted in price increases for a broader range of imported inputs, squeezing already thin profit margins.

Energy blackouts are now a continual threat to economic activity. By April 2022, the country was generating electricity at less than half its normal capacity. Rebels have blown up power lines, while high fuel prices have stalled activity at two major liquefied natural gas power plants in Yangon.

Rebels have also attacked fuel stations, tankers, installations, and their staff. Moreover, a boycott of energy bills – as part of the resistance movement – is reported to have cost the government around US$1.5 billion in lost revenues over the year up to April 2022. Revenue collection has also been disrupted by strikes at utility companies.

The outlook largely depends on the political environment. Given that the military appear unwilling to compromise with the opposition, civil unrest and the guerrilla war will continue. Foreign investors and tourists are unlikely to return under those conditions.

Pressure on Western companies to increase sanctions on Myanmar is likely to grow after the regime executed four pro-democracy activists in late July 2022. The US has sanctioned military officials and companies, condemned human rights abuses, but could do much more – such as sanctioning Myanmar’s oil and gas revenues and increasing aid to the opposition movement. The UN has similarly criticised the junta but has hesitated to directly intervene in Myanmar.

The country re-opened to tourists in April 2022 but given the uncertain security situation and widespread calls for tourism to boycott the country, it is unlikely that tourism receipts will provide any relief to the economy.

Commercial Risk – Downgraded from 5 to 4

Commercial risk has increased significantly since the coup, amid a deterioration in the ability of government ministries and the banking and legal systems to function effectively. Thus, many foreign companies are leaving.

In July 2022, the World Bank reported burdensome trade license requirements, the abandonment of the managed float exchange rate regime, and the imposition of foreign currency surrender rules have resulted in shortages of key imported inputs and inhibited exporters. Uncertainty among businesses has increased due to the rapid issuance of new policy instructions, including exemptions to previously imposed restrictions, followed by subsequent attempts to revoke those exemptions.

Despite bank-branch re-openings and several interventions from the Central Bank of Myanmar, physical currency remains in short supply and access to banking services also remains limited.

Additionally in January 2022, the US issued a formal business advisory for Myanmar. It warned of the heightened risks associated with doing business in the country. The advisory emphasized the reputational and legal risks of doing business and utilizing supply chains under Myanmar military control, particularly in any enterprises related to gems and precious metals, real estate and construction, and arms and military equipment.

In April 2022, the country’s military administration acted to tighten its control over movements of foreign currency. In a notification published in state media, the Central Bank of Myanmar ordered banks and other holders of foreign currency to convert these deposits into the local kyat currency. The official central bank exchange rate for the kyat is currently 1,850 per dollar, but this tends to be well below the unofficial black-market rate. The exchange rate hit nearly 2,500 kyats per US dollar in late July 2022, an increase of more than 80% since last year.

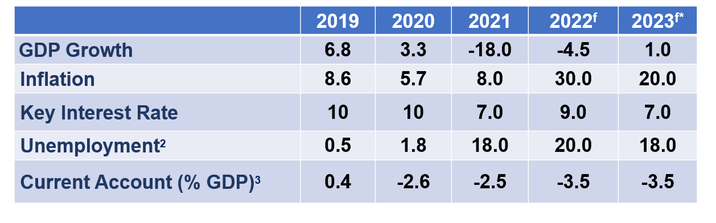

Latest economic data

f forecasts

* Worldbox Intelligence

2 World Bank

3 Statista

Source: World Bank/Asian Development Bank, except where stated

About Worldbox Business Intelligence

An independent service, Worldbox Business Intelligence provides online company credit reports, company profiles, company ownership and management reports, legal status and history details, as well as financial and other business information on more than 50 million companies worldwide, covering all emerging and major markets.

Worldbox was founded in the 1980s, with the vision to become a global business provider. Its ability to deliver data in multiple languages in a standard format has strengthened its brand.

Source: Worldbox

Write a comment